COVID-19's Impact on Family Medicine Residents' Wellbeing

Health disparities and discrimination continue to exist throughout all walks of life, and in medicine it’s no different. As an African American 1st generation female in medicine, it has always been an interest of mine to become knowledgeable in areas which may impact my patient panel.

Health disparities and discrimination continue to exist throughout all walks of life, and in medicine it’s no different. As an African American 1st generation female in medicine, it has always been an interest of mine to become knowledgeable in areas which may impact my patient panel.

I am the current Chair of the Diversity and Inclusion Committee at the Northwestern McGaw Family Medicine Residency Program at Delnor, where our goal is to engage in meaningful discussions. This committee strives to help residents understand their implicit biases and how these shape interactions with others. It works to stimulate growth and insight on inequities and diversity while exploring various topics of social determinants of health with an ultimate goal of application to our local Kane County area. As the COVID-19 virus progressed and necessities arose, our shift in focus was also redirected. The pandemic created hindrances in areas of work life balance, added tremendous stress on the healthcare system by increasing demands on resources, and further highlighted disparities and inequities. As a result, it presented situations in which my fellow co-residents faced forms of discrimination in medicine. It was at this time that I wanted to explore the implications that this pandemic created toward our family medicine residents (FMR) across the United States.

Previous studies have identified that minority physicians are subject to greater experiences of discrimination perpetuated by both patients and colleagues alike (1, 2). These experiences are known to have negative impacts on an individual's wellbeing, but studies suggest that teaching and addressing implicit bias within residency education has positive benefits (3, 4). The current pandemic has placed additional stress on physicians, including increased anxiety, social isolation, and fear of spreading the virus to family members (5).

The purpose of this study is to investigate the impact of COVID-19 on family medicine residents’ wellbeing and potential experiences of discrimination. We aim to better understand the impact that this pandemic is having on family medicine residents’ training experience, specifically those from underrepresented minorities. With the help of my team, I have learned the nuances of an Institutional Review Board (IRB), how to construct survey designs, navigate REDCap data collection, and review statistical data. I now further appreciate research and also acknowledge that though it is not an easy feat, it can be quite rewarding in the end.

Methods

Study participants were recruited in March 2020 via a snowball sampling methodology, utilizing several sources, including social media outlets (IAFP, Program Directors’ list-serves, Twitter) as well as personal contacts. Inclusion criteria consisted of the ability to provide informed consent and active enrollment in an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Family Medicine Residency Program. Exclusion criteria consisted of individuals who are not in an ACGME-accredited program.

The survey instrument was created using a collection of previously validated survey questions, which included information on participant demographics, perception of discrimination, COVID-19 exposure, access of personal protective equipment, HERO Daily Experience Index an instrument which evaluates an individual’s wellbeing and health in the workplace, and lastly COVID-19 impact on daily activities.

Preliminary Results

Snowball sampling size of 75 participants, of which 62 participants completed the full survey in its entirety. Our sample included a geographically diverse group, with representation from 17 states. Respondents represented 8 religious’ affiliations. A majority (79%) indicated English was their first language. Residency class participation included doctors of osteopathic medicine (43%) and allopathic medicine (57%). Representation from first, second- and third-year residency classes respectively (40%, 37%, 27%) and reported marital status as 37% married while 52% selected single. Though small sample size, greatest percentage of responders selected female (69%) as identified gender, while others reported being male (26%), non-conforming (3%) and other (2%). Average age cluster of responders were between 25-34 (79%) with the second largest cluster 35-44 (10%). Predominance of participants identified as White (60%), Asian (19%), or African American (4%) race. Majority sexually identified as Heterosexual (83%), with smaller percentages of Bisexual (5%) and Homosexual (3%).

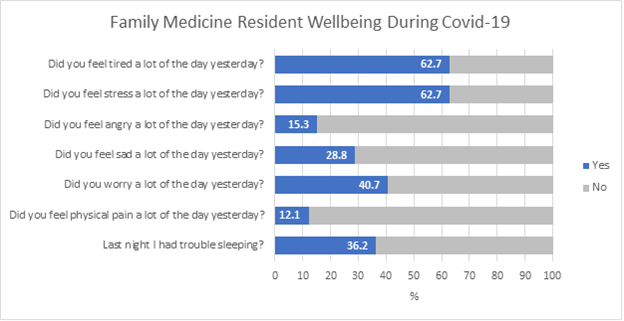

Initial survey instrument was implemented to evaluate family medicine residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. In figure 1, residents reported feeling tired (63%) and stressed (63%) in greater frequency than anger (15%) or in physical pain (12%). Our survey design doesn’t support causal inferences, so we aren’t able to directly link wellbeing metrics with Covid-induced stress. However, the data provides a snapshot of resident wellness during the early stage of the pandemic. This information can help tailor wellness interventions moving forward. Identified limitations to this study include cross-sectional survey, smaller sample size thus unable to calculate response rate. Stay tuned, as the remainder of the data continues to be analyzed.

I sympathize with my fellow co-residents across the United States and attest to the burden this pandemic has placed on our lives. I acknowledge my own experiences during residency mirrors the data provided. Despite our programs efforts to shelter us from this traumatic experience through counseling, time off, pregnancy limited exposures, and personal wellness.

Figure 1: Family Medicine Resident Wellbeing During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Future Plans

Our ultimate goal is to disseminate the research findings at the Family Medicine Residency research forum. Highlighting COVID-19’s implications on resident’s wellbeing, demographic impacts and exposures to discrimination.

Resources

1. Crutcher RA, Szafran O, Woloschuk W, Chatur F, Hansen C. Family medicine graduates' perceptions of intimidation, harassment, and discrimination during residency training. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11:88. Published 2011 Oct 24. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-11-88

2. Cook DJ, Liutkus JF, Risdon CL, Griffith LE, Guyatt GH, Walter SD. Residents' experiences of abuse, discrimination and sexual harassment during residency training. McMaster University Residency Training Programs. CMAJ. 1996;154(11):1657-1665.

3. Whitgob EE, Blankenburg RL, Bogetz AL. The Discriminatory Patient and Family: Strategies to Address Discrimination Towards Trainees. Acad Med. 2016;91(11 Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 55th Annual Research in Medical Education Sessions):S64-S69. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001357

4. Sherman MD, Ricco J, Nelson SC, Nezhad SJ, Prasad S. Implicit Bias Training in a Residency Program: Aiming for Enduring Effects. Fam Med. 2019;51(8):677-681. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.947255

5. Sanghavi PB, Au Yeung K, Sosa CE, Veesenmeyer AF, Limon JA, Vijayan V. Effect of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic on Pediatric Resident Well-Being. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520947062. Published 2020 Jul 30. doi:10.1177/2382120520947062